Top 10 Tips for Writing a First Collection

October 2020

Since releasing Biceps back in March, several friends have asked for advice on putting together a first collection. Good question: how the hell do you get a manuscript to the stage where a publisher will take it? I want to try and help demystify the process for other first-time writers with a debut collection on the go, so I’ve put together a Top Ten Tips for Putting Together a First Collection based on my own experience. These aren’t the be-all-and-end-all of how to write a collection, more just observations on what I did and what worked and didn’t.

1 | Don’t Do It Too Early

When I started writing Biceps, I’d been performing poetry for nine years. Nothing from my first six years went into the book, because frankly the stuff I wrote aged 19 wasn’t as good as the stuff I wrote aged 28. As you grow, your writing (hopefully) gets better, so it’s valuable to have a few years of practice behind you before taking on a book so that you’re bringing stronger, more experienced work to the page.

2 | Keep the Pen Light

The best gift you can give yourself is a new pocket notebook from your nearest branch of Flying Tiger (they retail for £2 a pop). In “Covid-times” I recommend Googling pocket notebooks. Buy one, put it in your back pocket, take it everywhere with you and note down any interesting things you see. Turn it into a diary if you like. When you burn through that notebook, grab another and keep at it. Accept that 99% of what you’ll write will be junk and that’s ok – 1% might be worth returning to. Focus on quantity over quality to start – I really recommend doing National Poetry Writing month (NaPoWriMo), finding a “30 poems in 30 days” group online or finding free resources like the Couch to 80k or 100 Day Writing Challenge to keep the pen moving.

3 | Mine the Gold

Quantity is great and all, but no-one wants to read a 500 page manuscript of brain-farts pulled out of the bottom of your sleeping bag (sorry). So now’s the time to mine that 1% of gold from your notebooks, workshops and scribblings on the backs of napkins. I recommend making an Excel sheet and listing everything you’ve ever come up with writing-wise. Doesn’t matter if it’s full poems you’re 100% happy with, half-finished stuff or just ideas you might want to work on in future – get it all down. (When I did this, I had around 170 bits and pieces on there, some just odd words or phrases). Take a look over your sheet and pick out a top 40 poems/ideas you like that might, maybe work together in a book.

4 | Spot the Connections

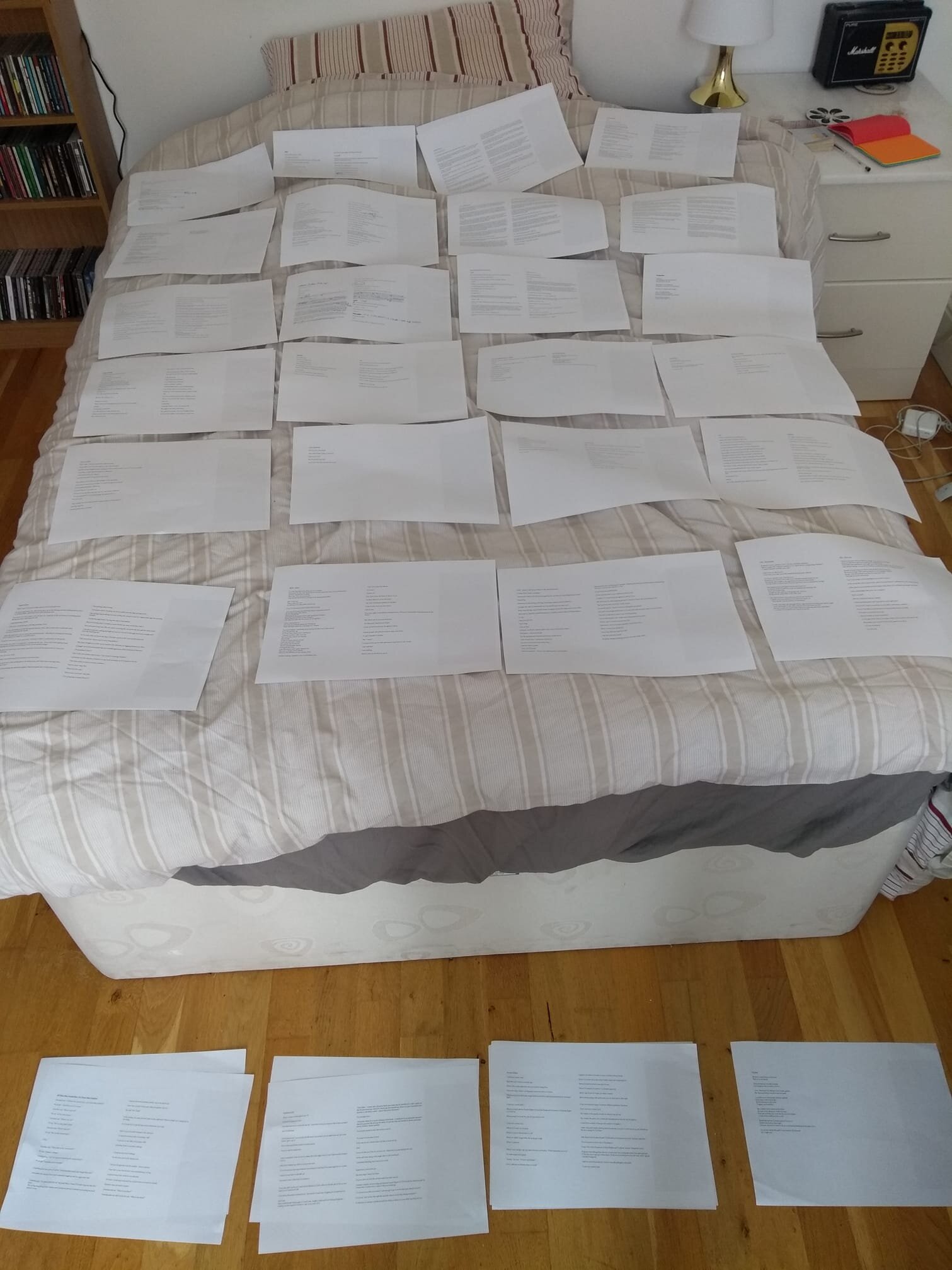

Now for the fun bit: print out your top 40 (I recommend printing one-sided and using your workplace’s printer if you can), lay them out on your bedroom floor, get yourself a cuppa and read through them all. Try and spot where connections exist between the poems: you might spot a turn of phrase, an image, an idea or a character recurring across several pieces. Start placing overlapping poems together however makes sense to you.

5 | Find the Shape

Grab yourself a big A3 sheet of paper and start making notes about the piles you’re making. Why are you choosing to group your poems in these ways? Try to note down what you think the big themes your poems explore. When I did this, I found the poems basically fitted into three piles: poems about making, poems about breaking and poems about building. From that, I knew Biceps was going to be in three parts called Make, Break and Build. Finding a shape for the collection will help you think more about the book’s overall structure and the experience readers will have as they navigate through it. It’ll also make your job easier: poems that don’t quite fit your big themes might be better saved for future projects.

Biceps on my bed in 2018

Biceps on my bed in 2020

6 | Commit to the Project Publicly

This is some people’s worst nightmare: but I found that telling people “I’m writing a poetry book” had real advantages. First, I found most of my friends were excited to hear it and their enthusiasm gave me a nice boost. Second, I felt like I’d make a more public commitment so needed to stick with the project – I didn’t want to let people down and that made me more determined to finish the manuscript. Third, I found that other writers recognised I was serious about the work, so were happy to help provide feedback and guidance which shaped the book enormously.

7 | Get Good Version Control

Very boring, but it’s really important to think about how you’re practically going to manage this project over the months or years you’re working on it. That means working out where you’re going to save / back-up your files and how you’re going to keep track of the various versions of the manuscript you work on. Personally, I prefer to work in Word and I’d email myself a revised version of the manuscript each time I worked on it as a back-up. I labelled the first version of the book “Version 00a”, then “Version 00b” and so on until I was happy to share it with my first editor for feedback – then I called it “Version 1”. Then when I edited that, it became “Version 1b”, then “Version 1c” and so on until I was ready to share it with another editor, when it became “Version 2”. It’s SO DULL but important to be consistent – you don’t want to end up scrabbling around and opening a file called “v1 FINAL EDIT 23.6.20 COMPLETE”, then find it’s an old version.

8 | Get Feedback

Got a file on your laptop that you’re happy to share with another human? AMAZING, WELL DONE YOU! Now for the tricky bit, sharing it with other people. I was very lucky here – I knew four talented writers that I definitely wanted to read the book and who were happy to take a look – but I know not everyone has that. If you don’t know that many other writers, I’d recommend just asking 3 or 4 other people whose opinions you value to take a look. Ask them for tough love – you’re not looking for a pat on the back, you’re looking to understand what is and isn’t working yet. Also, don’t be afraid to contact writers you love and ask them for advice or feedback – I was lucky enough to be on the same train as a poet I love and a cheeky ask landed me their email address and feedback down the line.

9 | Edit the Shit Out

My favourite test for editing is this: ask yourself “what’s this poem about?” If you can’t answer that question clearly, the poem isn’t working yet – it may have too much going on and need simplifying or might just be a bit confused. Give the poem a clear mission statement: “This poem is about x.” Then go through its stanzas. Check if they’re all contributing to that overall mission statement whilst also saying something distinct from the other stanzas. If not, those stanzas are for the chop.

Next, go through the individual lines. Are each of them contributing to the overall point of the stanza whilst saying something distinct from the other lines in that stanza? If not, uh-oh that’s a darling to kill.

Finally, zoom it right out. Think about what the book overall is about. Is every poem adding to the point of the book and saying something distinct? If not… well you get the point.

Also, you might find that the poems you liked best at the start feel a bit out of place by now. They might feel weaker or not fit the themes as well as your newer stuff. It’s ok to let those go.

10 | Make the Submissions Manager’s Job Easy

Once you finally hit that “Submit” button, your manuscript is going to thunk into the inbox of another human being. If you’re submitting to an indie press, chances are there’ll be one or maybe two people working at the company overall, so they’ll be reviewing manuscripts whilst also managing book releases, working with distributors and managing pretty much everything else involved in running a small business. Your manuscript will be amongst hundreds, if not thousands of others that they’re going to look through and they’re busy. So you’ve GOT to make it easy for that other human to select your book.

First, follow the submissions guidelines. If a page size or font is required, for God’s sake follow it. If you don’t, you may well be rejected outright and all your months of editing will be for nought. Also, read up on the publisher and think about why you want to work with them (being a fan of their books is a good start!) If it’s obvious from the website that the publisher is run by womxn, starting your letter with “Dear Sir” is a dead cert for rejection.

Second, make your book easy to read. If the request is for 40 pages minimum, don’t submit 80 pages. If you do, you’re asking someone to sit there and spend twice as long reading your book as others on the pile – do you really think it’s THAT good? Also, look at the publisher’s books and how they work. If they tend to publish books with poems that tend to last 1-2 pages, sending a book of poems that last 4-5 pages will feel like wading through treacle for them. Again, this is all part of being a fan of the publisher – if you’re not into the type of books they make, it’s important to think about whether you’re wasting your time and theirs submitting.

And that’s it – those are my Top Ten Tips for making your first collection. I hope they’re helpful and good luck with your book!